Review: James B. Thompson’s ‘painting’ as a verb at Hallie Ford Museum in Salem

Frank Miller, capsule Willamette University

http://www.willamette.edu/cla/arts/faculty/thompson/index.php

Accessed: 24.11.2010

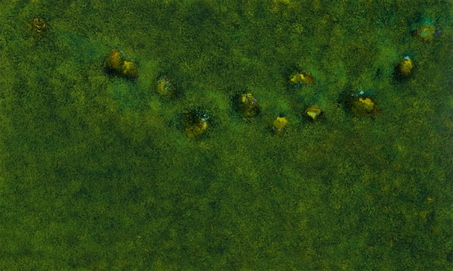

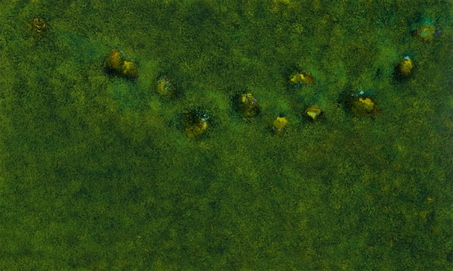

James B. Thompson, treat “Swale,” 2008, acrylic on canvas.

As painters immersed in the 20th century’s abstract revolution stopped painting things that looked like things, several interesting things happened.

First, art — or this type of art — relinquished its sense of place. Even if the artist was thinking about a mountain or a street corner or a pillow on a bed, there was no mountain or corner or pillow to be seen. Impressionists fuzzed up the landscape. Cubists diced it and reassembled it in funny ways. Abstract artists packed it in a steamer trunk and sent it off on a one-way voyage to Yesterdayland.

Second, space became intellectual, not actual. Painting had always been an illusionary act – how can we fool the eye into seeing what we want it to see? — but now the illusion was that spatial relationships as we ordinarily think of them didn’t exist. Artists such as Mondrian and Klee were consumed with the idea of how space works – they could be downright mathematical about it – but they produced a geometry, not a landscape, and it was a geometry of the mind. (As a side benefit, abstraction also strengthened realist painting, because for the first time serious painters had to ask themselves why they were painting realistically, and then either come up with a good answer or start doing something else.)

Third, painting became accidental. Yes, Jackson Pollock had ideas in mind, and no, not every one of his drip paintings worked the way he wanted it to. But the chance of the throw became a central aspect of the process. It was the I Ching-ing of the art.

Except.

As abstraction became less a revolutionary act and more a way of approaching art – in other words, as it matured it also opened up. It could be about all sorts of things, including landscape or whatever else was in the artist’s mind, whether anyone looking at the finished product realized it or not. And that’s an interesting question: If viewers don’t know there’s a level of thought below the surface of the paint, how can they tell what they’re seeing?

The paintings and prints in “The Vanishing Landscape,” James B. Thompson’s exhibition that continues through May 17 at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, raise precisely that issue. They’re ravishing things, especially the paintings — the sort of work that people like to call eye candy, although that’s a curiously dismissive way to think about art: What’s wrong with pleasing the eye, especially if you’re also doing other things at the same time? And Thompson’s art does a lot of other things, even if you’re only thinking about its surfaces. It’s a considered and sophisticated grappling with matters of space, color and mark-making — the difference, you might almost say, between a mar and a mark.

Underneath those lovely surfaces, marring is very much on Thompson’s mind. A native Chicagoan, Thompson has been on the art faculty at Willamette University in Salem since 1986, and he’s come to think of himself very much as a Westerner. What he sees, as he puts it in his artist statement for this show, is the transformation and disappearance of the region’s landscape “as planned developments, agribusiness and even golf resorts replace small town life, rural communities, family farms and forests.”

The tradition of landscape painting doesn’t deal adequately with the disappearance of land, he believes: Instead, it tends to depict idealized, unsullied evocations of what remains, so that we see a romanticized pastoral dream instead of the radically altered reality. A long tradition in photography has witnessed and recorded the sometimes brutal reshaping of the land, and representational painters such as Michael Brophy have tackled the issue of land use and abuse head-on.

But Thompson seems to want something at once deeper and more subtle — a philosophical undercurrent that transforms the act of artmaking into a reflection of the way we change the land. “The method of rendering abstract paintings and prints,” he writes, “is a celebration of the very act of change since this creative process involves the kind of continual mark-making that generates new sets of problems on the surface of each piece.”

In other words, you make marks – on the canvas or the land – and each mark is a risk. After all, the landscape of small towns and family farms that Thompson laments in passing was itself a reshaping of an earlier landscape far less decided by human intervention; one that might itself have been lamented as it faded before the ax and plow. So you think out each step, varying your mark-making according to some sort of loose plan, and you aim to come out with something beautiful. You don’t destroy the canvas. Chance, in the Pollock sense, is part of it. But instead of a big burst – a strip-mining of the image – it’s a considered improvisation, like good chamber jazz, each change partly determining what the next change will be.

How do Thompson’s paintings and prints emerge from this philosophical improvisation? Well, they’re gorgeous – and gorgeous in a way that invites repeated looking, because the more you look, the more you see. That’s a bit like looking, really looking, at the land.

The show’s 14 paintings, which range from about 2 feet square to 3 feet by 5 feet, are acrylic on canvas, and they’re richly layered, with a thick surface shine that makes them look almost like brightly fired ceramic tile. Yet they’re also nubbled, mottled like leather, with a suggestion of rises and hollows, or of something granular, like dirt. Their color is immediate, deep, voluble, seductive: oranges, reds, blues and greens that shout out their identities. Streaks, marks, splotches, running fences, finely scratched swirls like calligraphy, viewed in a certain frame of mind, seem topographical. It’s as if you’re seeing a landscape from an overflying airplane: lakes, rivers, roads, rises, habitations. The two dozen smaller intaglio prints are less deeply saturated in color but more significantly and lavishly marked, and at times they seem almost biological, in a microscopic way: They increase the illusion of some sort of exotic map-making.

Thompson suggests his underlying concerns through his titles: “Prairie,” “Wetland, “Aquifer,” “Range,” “Ridge,” “Karst” and the like. Yet the question remains: Does the viewer get any of these connections from looking at the art? You can easily view these prints and paintings and appreciate them as beautifully executed works that are simply about themselves. They’re abstracts – question marks. And their beauty raises another question: Are they, then, any less romanticized about the state of the land than the traditional landscapes Thompson finds so misleading?

Perhaps an answer lies in Thompson’s sense of movement, of making marks that lead to other marks in a dance of continuing small decisions. It’s a way of thinking about how we interact with the rest of the world, and it applies to intereactions far beyond canvas and paper. It’s “painting” as a verb, not as a noun. And it’s how we paint – how we make our marks – that makes the difference.

— Bob Hicks